The Disparities

in DETENTION

Youth of color are disproportionately impacted by the juvenile justice system. Data on differences in offending only tells part of the story.

Black youths face multiple layers of that ultimately make it more likely for these youths to be subjected to policing, punishment, and arrest compared to white youths. [1]

Even after accounting for demographic, family, and neighborhood condition predictors, there are still substantial residual arrest differences between youths of different racial and ethnic groups. [2]

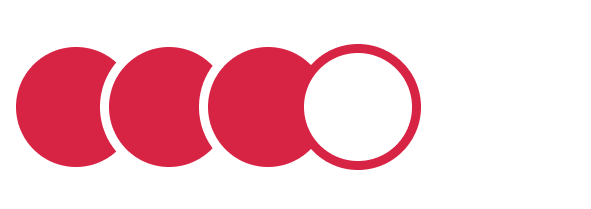

Research [3] by The Sentencing Project found that compared to white youth:

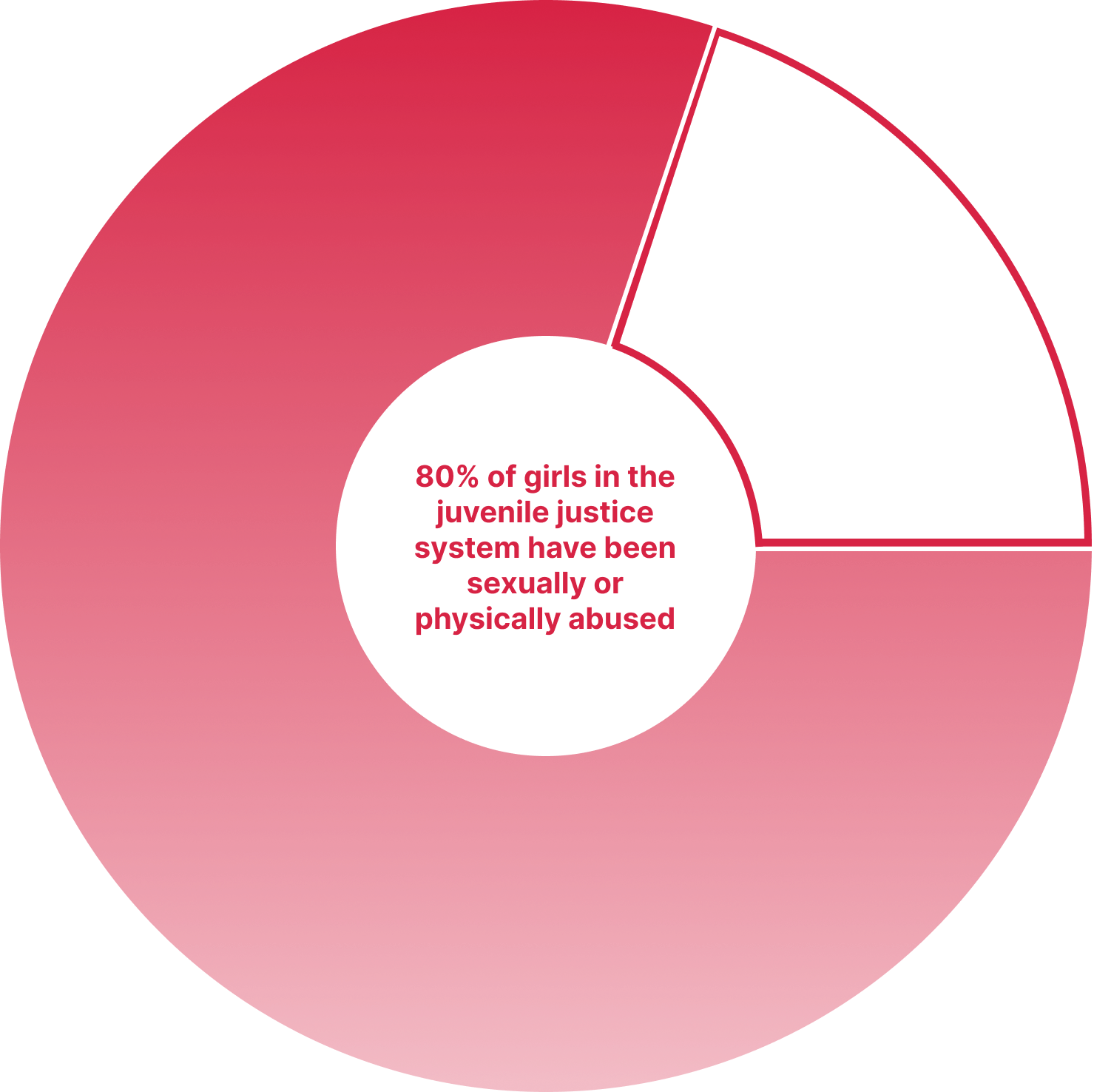

Discussions and investments into juvenile justice reform have historically focused on boys. [4] Despite only representing 28% of the delinquency cases handled by juvenile courts, double standards and a lack of gender-responsive services create unique challenges for girls within the juvenile justice system. [5]

In 2015, the confined in residential placement were being held for nonviolent offenses. [6]

1 in 3 of these placements were due to technical violations and status offenses, like skipping school and running away. [7]

These are children who pose little to no threat to public safety, but are still exposed to the harmful, often re-traumatizing experience of confinement. [8]

Girls who identify as LGBTQ+ also experience disparities in treatment.

Non-heterosexual girls are twice as likely to be arrested and convicted as other girls who had engaged in similar behavior. [9]

Overlooked and continuously failed, are falling through gaps in the child-welfare [10] The juvenile justice system has often, and wrongly, been depended on as an alternative to sustainably safeguarding children with unaddressed trauma and/or unmet mental, physical, and socioeconomic needs.

According to a report by the Vera Institute [11]

Rather than focusing on prevention and rehabilitation, society overrelies on incarceration. This criminalizes children for behaviors related to forms of trauma and violence that disproportionately harms girls and gender-expansive youth. [12]

References

- Monk, E. P. (2018). The color of punishment: African Americans, skin tone, and the criminal justice system. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(10), 1593–1612. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2018.1508736

- Kirk, D. S. (2008). The neighborhood context of racial and ethnic disparities in arrest. Demography, 45(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2008.0011

- Rovner, J. (2021). Racial Disparities in Youth Incarceration Persists. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/racial-disparities-in-youth-incarceration-persist/

- The Vera Institute of Justice. (n.d.). Vera’s 10-Year Strategy to End Girls’ Incarceration. Vera Institute of Justice. Retrieved May 11, 2021, from https://www.vera.org/publications/veras-10-year-strategy-to-end-girls-incarceration/veras-10-year-strategy-to-end-girls-incarceration/veras-10-year-strategy-to-end-girls-incarceration

- Ehrmann, S., Hyland, N., & Puzzanchera, C. (2019). Girls in the Juvenile Justice System. National Report Series Bulletin. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/251486.pdf

- Ehrmann, S., Hyland, N., & Puzzanchera, C. (2019). Girls in the Juvenile Justice System. National Report Series Bulletin. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/251486.pdf

- Ehrmann, S., Hyland, N., & Puzzanchera, C. (2019). Girls in the Juvenile Justice System. National Report Series Bulletin. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/251486.pdf

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2015). Girls and the Juvenile Justice System Policy Guidance. OJJDP Girls Study Group Series. https://rights4girls.org/wp-content/uploads/r4g/2016/08/OJJDP-Policy-Guidance-on-Girls.pdf

- Himmelstein, K. E. W., & Brückner, H. (2011). Criminal-justice and school sanctions against nonheterosexual youth: A national longitudinal study. Pediatrics, 127(1), 49-57. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2306

- Lutz, L., Stewart, M., Hertz, D., & Lyman, L. (2015). The Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM). Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5eb2bae2bb8af12ca7ab9f12/t/5f66baedae8624210b2ea987/1600568047996/CYPM-Abbreviated-Guide+%282%29.pdf

- Rosenthal, L. (n.d.). The Initiative to End Girls’ Incarceration. Vera Institute of Justice. Retrieved May 11, 2021, from https://www.vera.org/projects/the-initiative-to-end-girls-incarceration

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2015). Girls and the Juvenile Justice System Policy Guidance. OJJDP Girls Study Group Series. https://rights4girls.org/wp-content/uploads/r4g/2016/08/OJJDP-Policy-Guidance-on-Girls.pdf